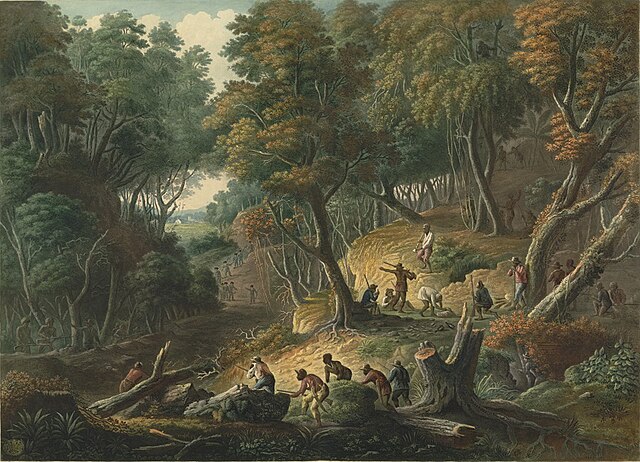

In the foggy haze of the Blue Mountains, British redcoat soldiers trekked through hazardous terrain in search of an elusive Maroon village.

As they moved through the dense bushes of the dark mountain ridge, they trusted that their superior weapons would guide them to victory. But every step they took deeper into the mist led them into a nest of camouflaged warriors waiting to strike.

The Jamaican Maroons were runaways who valiantly resisted slavery. The slave system in Jamaica was as deadly as it was dehumanizing. Enslaved people faced family separation, public beatings, torture at seasoning camps, and sexual assault.

The only thing more dangerous than being a slave was being a captured runaway. Under British law, authorities hanged, maimed, or even slit the noses of recaptured runaways as a form of barbaric punishment.

Shockingly enough, historians reveal that the same types of brutal amputations inflicted in the Belgian Congo also occurred during Caribbean slavery. Both men and women who failed to escape had their limbs amputated to discourage further attempts.

Given these horrific consequences, it was crucial for runaways to avoid recapture. Exploring the brutality of slavery and the powerful force of freedom can help us better understand the true mindset of a maroon.

The First Step Toward Freedom

Fleeing was the first step. Even those who managed to escape into the wilderness risked starvation as well as death from exposure or injury. Those who survived had two choices: east or west. Runaways who settled in the eastern Blue Mountains are known as the Windward Maroons, while those who travelled west to Cockpit Country are known as the Leeward Maroons. Although maroon communities still exist, these regions remain so hazardous and isolated that very few Jamaicans choose to settle here, even in modern times.

The treacherous nature of these mountain environments must be emphasized, as it exposes how desperately enslaved Africans longed for liberty. These Maroons did not wait for the monarch to grant them limited liberty. If they did, they would be waiting over a hundred years for anti-slavery laws to finally take effect around the 1830s. They refused the indignity of enslavement and decided that death in the deep precipices of the interior would be better than the plantations.

Hiding in the inhospitable mountain ranges was not enough to secure their safety. Yes, the high ridges of Jamaica’s Blue Mountain, John Crow Mountain, and Cockpit Country acted as a protective barrier shielding them from British surveillance. However, the British were not afraid to go searching for them.

Slave maroonage was a direct attack on the institution of slavery. It weakened colonial power by creating a shortage of workers and enticing plantation slaves to attempt their own plot for freedom. In addition to strategically using the island’s mountain scape as a military tactic, Maroons also had to master the art of guerrilla warfare.

Masters of Guerrilla Warfare

Guerrilla warfare involves using aggressive tactics to delay, distract, or bombard a larger army. The typical rules of engagement don’t apply here. This opens up new avenues for rebels to destabilize and thwart traditional strategies. Guerrilla tactics used by both the Windward and Leeward Maroons included ambushes, hit-and-run raids, concealment, and psychological warfare. The Cockpit Country was known among the British as “The Land of Look Behind” due to the high threat levels of spontaneous maroon attacks. The Maroons also utilized the abeng, an acoustic device made from a cow horn, to send coded messages across the vast mountain tops.

In terms of weapons, the Maroons had little issue acquiring guns and ammunition picked up during plantation raids. When they didn’t feel like using guns, they booby-trapped trails and released large boulders to fall on the advancing British army. They often built their villages with a single narrow path leading into and out of the community. This ensured they had a full view of any approaching force. On orders from their headman, the women were told to burn the village if the colonial forces got too close. As stated by Barbara Kopytoff, an anthropologist from the Penn Museum, the Maroons preferred to lose everything rather than allow their enemies to seize their belongings.

Warfare consumed their entire existence. The leaders of these towns, Cudjoe of the Leeward Maroons and Nanny of the Windward Maroons, ran their villages with little room for insubordination. Anyone committing crimes or resisting the headman’s authority was killed. If the headman was proven corrupt, he was also killed and replaced.

To limit the prevalence of insurgency within his own group, Cudjoe appointed English as the main language within the village. This ensured that no one tribe received preferential treatment.

In addition to guerrilla warfare, the Maroons had several other advantages on their side, one being the unorganized nature of the British militia. For starters, battles in Europe were rarely fought in this guerrilla style. European soldiers march and announce themselves, and wear bright coloured uniforms while employing a rigid and somewhat predictable form of military strategy. This did not work in the mountains. The bush was thick and disorienting, and they had to travel distant miles before even coming close to a suspected maroon foothold. By the time they encountered the Maroons, they were tired, demoralized and frazzled.

Moreover, the British force was not operating at full size. These maroon revolts were occurring all over the Americas, and England could only afford to send small groups of troops to Jamaica. Many of those men immediately became ill from new diseases they hadn’t encountered before. Many of them died before even stepping into battle.

As a result, the British encouraged plantation owners to double as military men. In their ranks, both slave and freed Black men were also persuaded to fight in the Maroon Wars of 1728 and 1795. There are stories of valiant slaves who fought with honour alongside slave masters. Despite this, it is believed that the freed Black men only halfheartedly battled the Maroons and the enslaved men absconded and joined the runaways at the first opportunity.

The small size of the inexperienced British force only exacerbated the advantageous position of the Maroons. However, nothing flourishes in wartime. The Maroons wanted peace and autonomy. Although they were a formidable force in battle, they were growing tired of the constant possibility of discovery and recapture. Similarly, the British knew that they were no better off. Their men could not secure any major victories over the Maroons, and plantation raids were becoming harder to control. A treaty was on the horizon.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

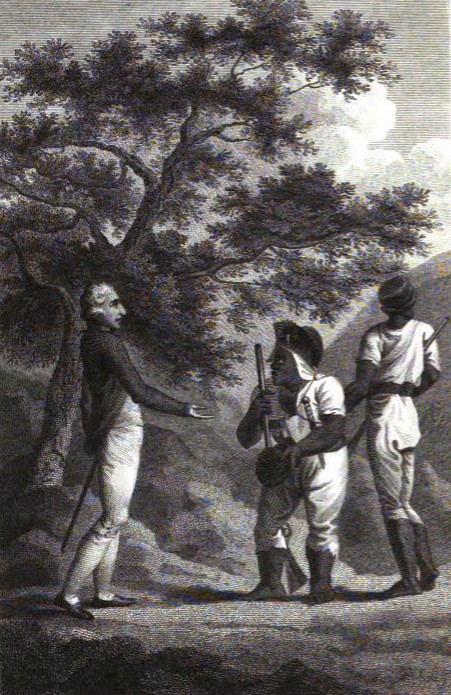

Locating the Maroons for war was difficult. Locating and persuading them to sign treaties posed an even greater challenge. Governor Trelawny waited intently as several attempts at peace talks were rejected by headman Cudjoe. Eventually, under the leadership of John Guthrie, Cudjoe’s village was captured, which made the Maroon headman a lot more receptive to making deals. On 1 March 1739, Cudjoe and Guthrie signed a treaty that would:

- Recognize the Maroons as a free and autonomous group.

- Allot them full ownership and control of the land within their villages.

- Allow them to openly participate in trade, which ended the need for plantation raids.

- Grant them full legal responsibility over their own people, except for imposing death penalties.

In exchange for these terms, Cudjoe agreed to stop accepting new runaway slaves and to return them to the possession of the British.

Shortly after this, similar treaties were signed by Quao, the new leader of the Windward Maroons.

These treaties effectively turned the freedom-fighting Maroons into slave hunters. Nanny of the Maroons was the only powerful voice opposing the treaty; however, Quao signed in her place.

This decision is quite controversial. It pins one group of Black people against another when both groups yearned for the same outcome: liberty. Some argue that Cudjoe and Quao doomed their fellow Africans to the disturbing perils of enslavement for another hundred years. Others point out that colonial forces often do not keep their treaty promises; therefore, it was foolish for Cudjoe to accept Guthrie’s terms.

These sentiments were reflected by many of the Maroons, who also saw the treaty as a deal with the devil. They disbanded from the Leewards and fled even deeper into the Cockpit Country.

Beneath this problematic period of confusion and sorrow, there are a few victories that the Maroons should be proud of.

Living Monuments of Freedom

The Maroons secured autonomy for themselves 94 years before the Crown recognized Black people as people. They continued to establish and control their villages, namely Nanny Town, Moore Town and Accompong, which still exist today. The Maroons preserved African spiritual traditions like Obeah and Kumina, both of which remain culturally significant. They turned a hideaway into a homeland, establishing themselves as enduring symbols of bravery.

Even amid economic growth and potential encroachment, Jamaicans understand the importance of these villages and actively fight to preserve them.

The plight of the Maroons teaches us that freedom is never given; it is earned. It also shows us that the road to liberation is not neat and linear. Liberations often involve difficult compromises and deals with unlikely parties.

The interior mountainous regions of Jamaica are not just beautiful tourist attractions. They serve as living monuments of Jamaica’s long history of rebellion. To explore other stories of liberation, like the secret link between the French and Haitian revolutions, stick around for my next post.