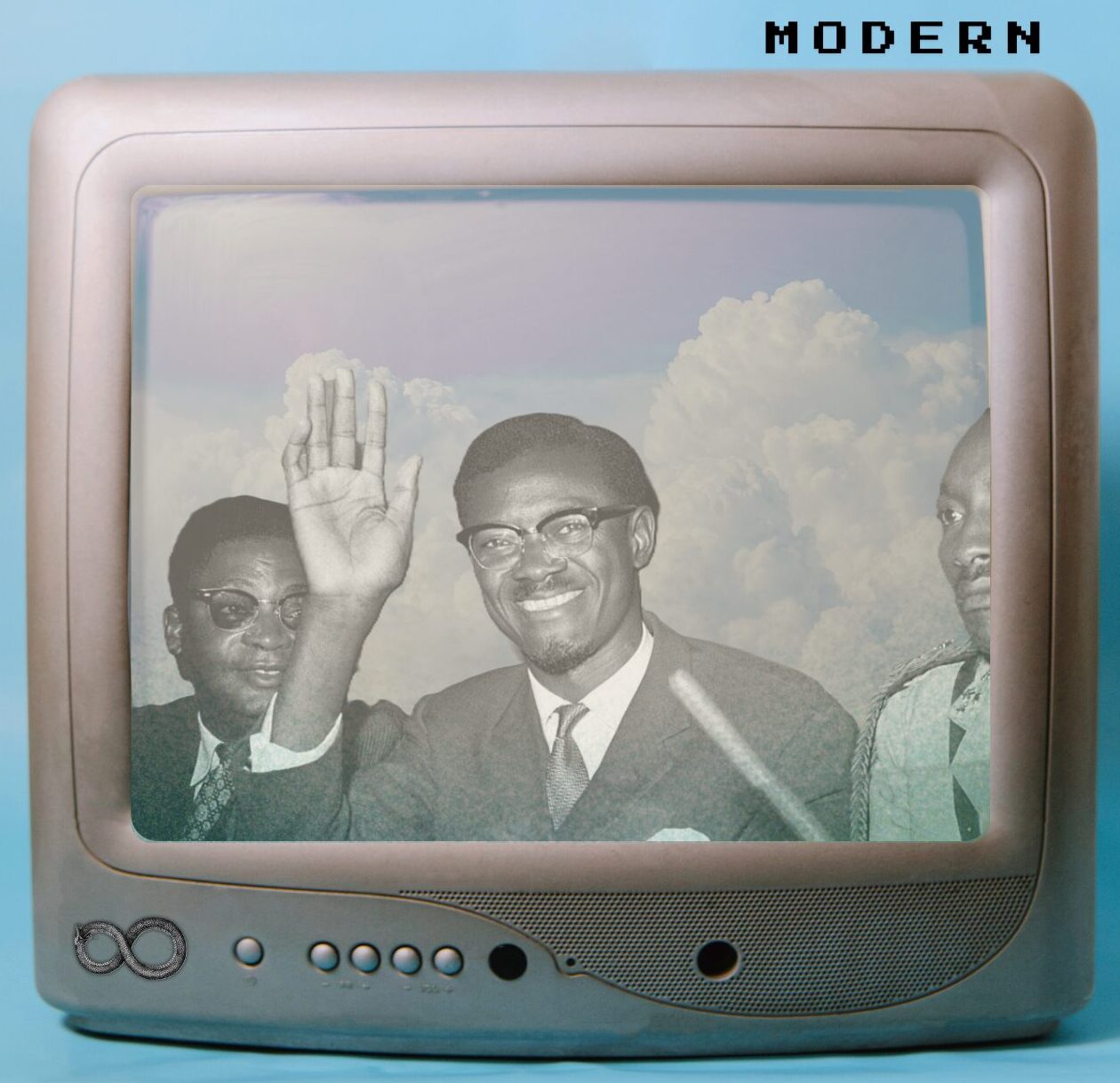

After decades of colonial control, the Congo finally elected its first democratic leader, Patrice Lumumba. His enemies assassinated him six months later.

He wasn’t a warlord, a gangster or a nepotistic implant. He was a common man and a proud member of the working class. To his people, he embodied the allure and familiarity of a long-lost friend. Outside of the Congo, he was making enemies in very powerful places.

He had high hopes and ambitious plans for his country. The Congolese people stood behind him, prepared for whatever struggles lay ahead.

So how did he find himself staring down the barrel of a firing squad 200 days after the election?

Lumumba wasn’t always a revolutionary. In another world, he could have lived a simple life like anyone else in any farming village in Katakokombe. However, in time, his nationalist ideals posed an ideological and financial threat to the Western world. His defiant nature and charming influence swelled the hearts of the Congolese people who yearned for freedom and statehood.

But every step towards liberation came at a cost.

His leadership attracted the malice and paranoia of Belgian officials, frustrated presidents and even the head of the CIA.

From Postal Clerk to Prime Minister

Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa was born on 2 July 1925 and later became the pan-Africanist martyr known as Patrice Emery Lumumba.

Despite his farming family roots, he carved out his own path towards higher education and politics. After years of working at the post office, he found an outlet for his anti-imperialist viewpoints by co-founding the Mouvement National Congolais.

Following a confusing and messy period of politicking, Lumumba gained enough political support across the country. In June 1960, he became the Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

He wanted his people to be free from racial subjugation. He also wanted African nations to have a fair chance to independently develop themselves into a strong political bloc.

Lumumba had ideas of a truly autonomous Congo, where the country would have full control over its resources and trade policies. However, ideas can be deadly.

30 June 1960 should have been a joyous day, officially marking Congo’s independence from Belgium. Unfortunately, Lumumba’s speech during this independence celebration would ultimately seal his fate. When he stood at that podium and delivered words of defiance and calls for justice, the Belgians effectively earmarked his death.

June 30, 1960: Target Acquired

On Independence Day, King Baudouin gave a speech that praised Belgium for righteously saving the Congo from its own demise. He commented on how King Leopold II “civilized” the nation and banished all the tribal problems the colony faced before European intervention.

His speech very closely mimicked a popular rhetoric known as the ‘white man’s burden.’ Whites in Europe saw themselves as saviours rescuing savages from their old world traditions. The term came about from Rudyard Kipling’s popular poem of the same name. In it, Kipling proudly states that it is the European duty to parent other races due to beliefs of white superiority.

Many Europeans at the time treated other groups, especially Africans, as both children and devils alike. They viewed colonization as a necessary responsibility to show non-Europeans the ‘proper’ way to live and be a good citizen.

This sterilized view of colonialism is as hilarious as it is insulting.

In his speech, King Baudouin exclaimed that Belgium saved Congo from the slave trade but failed to mention the millions forced into slavery under the orders of his own great-uncle, Leopold II.

Baudouin stated that Belgium entered Congo to bring peace and modernity while overlooking the murders, the amputations, the dehumanization…the human zoos.

With every word of his speech, Baudouin effectively buried the horrors of his country’s crimes. At the same time, he expected the Congo to thank him for granting their freedom.

After the King’s speech, it was Lumumba’s turn to set the story straight.

No one had scheduled Lumumba to speak, yet he still delivered an unforgettable presentation that called out the injustices of the Belgian regime. He reframed the King’s approach by reminding Belgium that they did not give Congo freedom; his people ferociously fought for it.

He exposed the racism, the forced labour, and the suffering. He proclaimed that the treatment his people received was worse than death.

Lumumba had plans that Congo would now have full control over its resources, would operate in its own interests and would expel all foreigners who could not learn to behave. The Congolese people excitedly applauded Lumumba’s speech. Their cheers erupted so loudly that he had to pause and start again several times. The people loved it.

Baudouin was not happy.

There is such a strange paradox at play here, where colonists can cut off the hands of children and see no harm, but become vastly offended only when someone mentions it.

Immediately after the speech, everything came crumbling down. Baudouin furiously marched out, which stalled the ceremony for an hour. The mainstream Western media labelled Lumumba as an ungrateful radical, and the Congolese army mutinied because they weren’t immediately given promotions. Making matters worse, areas such as Katanga (the rich mining region) were so turned off by Lumumba’s government, they seceded and turned away from the country.

Katanga was the Congo’s wealthiest province and contained the very resources Lumumba mentioned in his speech. Without control of those resources, Congo could not support itself financially and faced an enormous uphill battle.

Violence had broken out, and the Belgians used this as an excuse to reinforce their presence in Katanga by supporting anyone who went against the Lumumba government.

All of this instability would place another powerful target on Lumumba’s back.

Uncle Sam and the Three-Lettered Boogeyman

His plans were quickly unravelling at the seams, and with very few allies to turn to, Lumumba found refuge in an unlikely ally.

The Western world picked sides, and their allegiance leaned more towards Belgium than towards Lumumba. So when he asked for help to properly handle the mutinies and secessions, they said no.

He turned to the East and accepted weapons from the Soviet Union, which only deepened the hole his speech had put him in.

The United States was convinced he had been seduced by the red waves of communism. Larry Devlin, a CIA agent stationed in the Congo, routinely reported back to headquarters with tales of Lumumba’s lust to turn the country into a communist foothold. Lumumba was no communist; he was pragmatic. He was playing the most dangerous game of whack-a-mole, desperately trying to fix things as they were breaking.

Lumumba couldn’t keep up, and the damage was done.

Belgium hated him for rubbing their noses in the reality of their past brutality. America hated him for cozying up to the communists, despite refusing to help him in the first place. Soon, these two world powers turned their petty gossiping into a real objective to eliminate Patrice Lumumba, and thus, Project Wizard was born.

Africa’s Julius Caesar

Project Wizard was a covert CIA operation supported by Belgium and aimed at destabilizing the Lumumba government. The CIA, Devlin in particular, did not find random people to use as puppets. He focused on the men who stood beside Lumumba on that fateful Independence Day.

Joseph Kasavubu and Joseph Mobutu both knew and worked alongside Lumumba, yet needed very little nudging to turn their colleague into a sacrificial lamb.

With American bribes sitting heavy in their pockets, they stripped Lumumba of his position and dismissed him from the government on 5 September 1960.

Ironically, Devlin and the Congolese conspirators quickly noticed that support for Lumumba was still strong. So long as he was alive, they could not extinguish his influence.

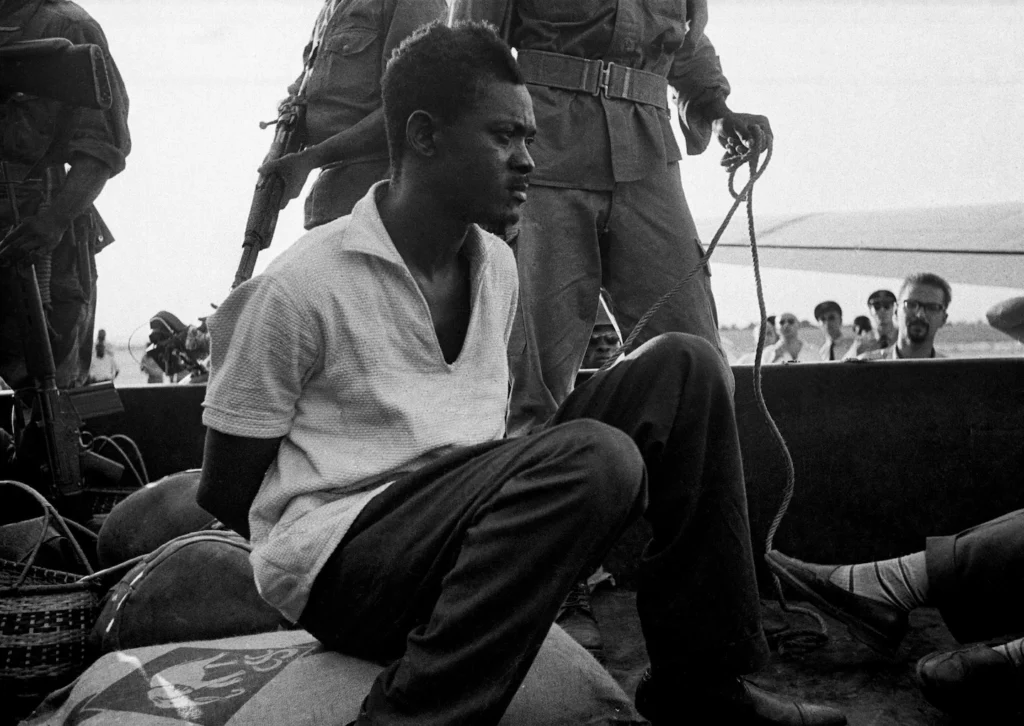

But they could make him suffer.

After months of detainment, Lumumba succeeded in carrying out an escape plan on 27 November 1960, but was recaptured shortly after.

To break his spirit, Mobutu sent Lumumba to the “home territory of his sworn enemy”, the state of Katanga. While Lumumba still had supporters in other regions of the Congo, Katanga was home to his harshest political rivals and Belgian officials who showed no love for the former leader.

In Katanga, he was tortured, beaten, led to a remote area and shot in a field of tall grass on 17 January 1961. His remains were dismembered and dissolved in acid in an attempt to quite literally remove all traces of him.

A Modern-Day Martyr

Patrice Lumumba still remains vibrant in the minds of the Congolese people. He symbolizes Africa’s greatest what-if. What if he served his entire term? What if the people of Katanga were more flexible? What if his friends refused American bribes? Where would Congo be today?

The patterns found in Lumumba’s downfall are not unique. The 60s, 70s and 80s are rife with tales of foreign intervention that destabilized entire countries. In most cases, Western organizations did not intervene to oust wicked warlords or to ‘spread democracy,’ they got involved to secure their own financial profits.

The resources harvested in African countries made the West so rich that it could not afford to let go of its most prized possessions. As colonization began to dissolve, an era of covert imperialism emerged. Western nations now use underground missions to ensure the continuation of a system that benefits their interests.

We must consider this when viewing the developments happening in the world today. When reading stories of the current civil wars and disastrous unrest, we must look back to recent history to try and locate the powers behind the scenes. This is not to say that the West is always involved.

We have to think back to the key events that altered the trajectory of a country. The events of 17 January 1961 altered the natural progression of the Congo.

Unfortunately, the stars misaligned for Lumumba.

Everything that could have gone wrong went wrong. Belgium’s sensitivity, Cold War fears, hysteria, CIA bribes and jealous friends all coalesced and turned a once-loved and respected leader into public enemy no. 1.

History isn’t just about what happened—it’s about understanding why it still matters.

If Lumumba’s story moved you, follow @freeforallhistory on Instagram for more freedom heroes, uncomfortable truths, and the moments that changed everything.

Still interested? Read my last post about the first-ever workers’ strike in history.